Date: 22/12/2024

Trip leader: Aidan Irrang

Party: Aidan (Trip Leader), Alex, Marty, Paul, Grace

The Newnes plateau stands around one thousand meters above sea level, separating the catchments of two wilderness rivers, the Wolgan and Wollangambe. Part state forest and part national park the plateau drops to the east into the Wollangambe Wilderness, with many fine canyons along Bungleboori and Dingo Creeks. To the north it merges into the Wollemi Wilderness, the largest declared wilderness area in the state. Magnificent canyons run down into Rocky Creek, a major tributary of the Wolgan River, the best known being Rocky Creek Canyon itself, a visually stunning but technically undemanding canyon full of families and tour groups all summer long. No such crowds are to be found in the other canyons. Only the occasional car parked along the Rocky Creek Trail reveals that there are canyoners out there.

Our day began on an old firetrail, now fenced off to prevent vehicle access and marked ‘Wollemi Wilderness Walkers Only’, the words written in spot-welds on sheet steel to survive bushfires. This and other abandoned roads snake out across the northern end of the plateau, overgrown with head-high saplings of eucalypt and wattle and woody shrubs like hakea and isopogon. Only the absence of mature trees reveals where the trail was originally bulldozed through the bushland. Nevertheless, the single-track running along the old road makes for rapid progress, with relatively few trip hazards, and it’s easy to follow the ribbon of absent tree canopy through the forest. We were too late in the year for the best wild flowers, but little spots of blue and purple remained amongst the green and grey vegetation. The seed pods from this spring’s red Waratah blossoms were visible all around us.

It was a cool and overcast morning, a blessing on a day that would get up to 28C by lunchtime. The old road wound around Galah Mountain and then off across the plateau, ending an hour later at a small clearing with a cairn. From here we set off bearing north-east bearing along a ridge. As the ridge was broad and flat we found only a few signs of footpads where other parties had walked, but the scrub was not overly thick and we actually overshot our grid reference for the turn down to canyon by a few dozen metres and had to backtrack. Off the ridge the steep slope was harder going, as we felt for footings amongst the loose rock, dry soil, sticks and leaves. Excitement rose as the cliffs on the far side of the canyon came into view and a large ‘pagoda’ rock formation appeared just below us.

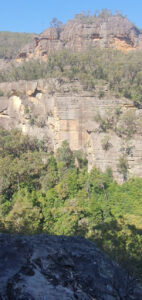

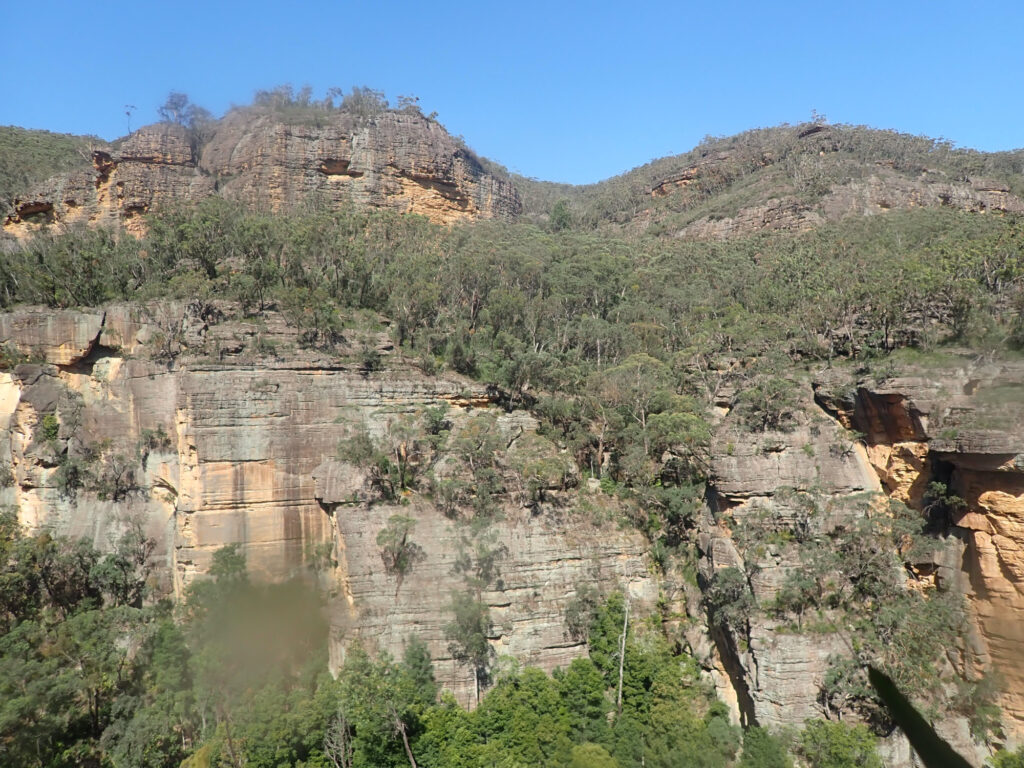

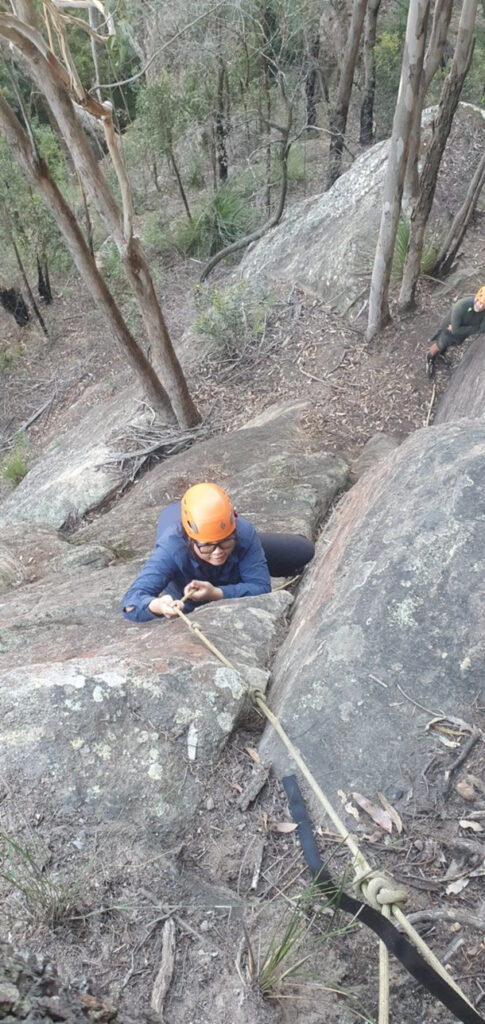

We got into a dry watercourse that led to the left of the pagoda and to the edge of the canyon. We were at the top of a twenty-metre cliff looking into an amphitheatre full of mature eucalypts, and a wind-sculpted arch of sandstone under the pagoda formation. The rocky edge of the canyon was made up of the formations that give this area of the mountains its name – the Gardens of Stone. Ornate, wind-sculpted rock formations made up of alternating bands of wind-eroded sandstone and harder brown ironstone, creating an almost irresistible temptation to rock-scrambling. It looked straightforward to scramble down on the other side of the amphitheatre, but a sling and maillon around a tree invited an abseil right where we stood. The sun was reaching full strength now, as midday approached, and each abseiler welcomed the shady overhang below the cliff when they arrived.

We looked forward to entering a cool, dark canyon but found we had a fair way to walk before reaching the first constriction. The creek started out as a brown trickle of water hidden beneath grasses and ferns which we crossed and recrossed, hardly able to see our feet, before the cliffs closed in and tall coachwood trees, trunks mottled green and grey with lichens, started to block the direct sunlight. The creek bed became a sandy strip with banks of dry leaf mould and was easy going. We walked through a cave created by a chunk of cliff the size of a small apartment building which had fallen to lean on the opposite wall of the canyon. The cliff supporting it was smooth, water-carved rock in complete contrast to the intricate, coffered pattern of wind-erosion on the face of the fallen block.

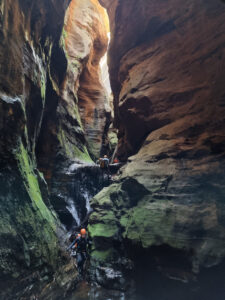

Eventually the creek plunged down into a dark slot and we welcomed the chance to abseil into the cool. Lunch was postponed until the bottom of the abseil, out of the heat. From here we waded and splashed through several cool, green, sandstone chambers separated by slides and climb-downs until we emerged again into an open section of the canyon dominated by large coachwoods.

The fires and floods of the past few years had left this section full of fallen trees, making for slow going as we detoured up and down the banks to avoid the worst tangles of trunks and branches. As the creek started to descend more steeply the watercourse ran through a chaos of car-sized boulders. These combined with the fallen timber to slow our progress. It was mid-afternoon before the bed of the creek was suddenly free of debris, an undulating slope of polished rock suggesting the approach to a waterfall, and we arrived at the main constriction. The slot opened up in front of us, dark and inviting, while the cliffs closed together above us, the smooth, water-carved faces of the rock meshing together to block further views.

A two-stage abseil led down into the canyon proper. A few metres of scrubby abseiling to a rock platform and then over the lip of the waterfall into the deep, cool canyon. Those in wetsuits took a welcome opportunity to cool off under the waterfall while those in thermals added an extra layer in anticipation of the cold to come. We made out way down the constriction, moving from one rock-room to the next by sliding down ancient, water-smoothed tree trunks, or setting short abseils from the slings and bolts left by previous parties. The undulating rock walls rose away above us fifty metres off more, sometimes joined by chockstones unable to fall to the bottom. Each deep pool and sculpted chamber was admired for its beauty until we arrived at the final abseil, over a polished lip of rock beyond a deep pool. People found ways to send cascades of water down over each abseiler as they descended the final drop, blocking the narrow channel above the pool and then releasing the water all at once, or simply plunging into the pool to displace a human body’s worth of water over the lip. A short wade between the high, narrow walls and we were in the open, standing on top of a chaos of giant boulders and looking out at the sunshine and high cliffs of Rocky Creek.

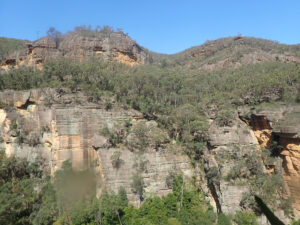

At this point, a few kilometres downstream from Rocky Creek Canyon, the creek runs through a narrow, forested valley between two hundred metre cliffs, dotted with trees that cling to narrow ledges or root themselves in near-vertical clefts. Birdsong could be heard from the trees on the valley floor and the warm air rose to meet us. After a snack break we crossed the boulder field and followed the base of the cliffs, stopping regularly to admire the rock on the far side, brightly lit by the western sun as it was now four in the afternoon. The climb was just as described, a steep, diagonal cleft in the cliffline above an exposed slab of grey, weathered sandstone whose slope steadily increased to leave a couple of metres of proper climbing before reaching the cleft. A rope had been left hanging down, making the climb a breeze, and after putting helmets back on we scrambled up one after the other, hauling our packs up with the rope. At the top of the climb we found ourselves below a further line of cliffs and followed these back into the canyon, high above where we had waded and abseiled an hour earlier. As we re-entered the forested part of the canyon a clear ‘drip line’ developed along the cliff base and it was easy walking until the canyon floor rose to meet us, and we were back in the creek.

It was now after five and time to find an exit from the canyon. We followed the creek upstream under the coachwoods until we reached the bottom of the first constriction. Just before entering the constriction we saw a dry waterfall, with a wide gully visible above it and obviously leading to the tops. Disturbed soil amongst the ferns and moss just to the left of the waterfall looked like a sign of foot traffic, and with the help of a handy log we climbed up to a ledge that connected to the gully. The ledge was sloping and where others had trodden before us the soft, green moss on the sloping rock had given way to slippery mud, calling for some careful footwork. But from here it was a simple, steep climb through dry bush to the end of the same ridge we had used to access the canyon. The ridge had us back at the old firetrail by half six, and from there we each walked at our own speed the final stretch to the car. As it was now early evening, albeit on the longest day of the year, we had avoided the heat of the day on the tops at both ends of the walk. The sun was low and the the yellowing light slanting through the forest gave it a quite different look from the overcast morning. Then it was a short drive back to camp and a long evening to talk over the highlights of ten wonderful hours in the bush.