by Chris (Old Mole) Cosgrove

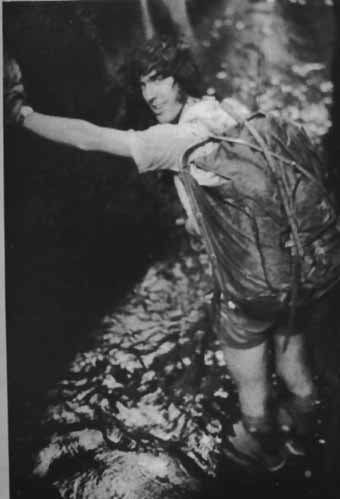

Above – Chris Cosgrove in a canyon, circa 1973, Reproduced without pemission from “Out and Beyond 1973” – SUMC annual publication. Photo attributed to BL.

The “Royal Traverse” is a classic Tasmanian megabash. It starts near King William Saddle on the Lyell Highway west of Derwent Bridge and finishes at the Gordon Dam near Strathgordon. In between lie the King William Range, the rarely visited Prince of Wales Range and the Hamilton Range. When myself, Peter (Fleabeard) Blackwood and Karsten Pedersen did it in January 1972, the Gordon damsite was just starting to get bulldozed while the nearby Serpentine Dam was already completed with the dreaded lake creeping back towards the original Lake Pedder.

This walk was initially proposed two years earlier by myself and Mark Fowler on a Federation-Arthurs traverse, Mark having learned about it from Helen de Clifford of the Hobart Walking Club on a trip to Precipitous Bluff just before. According to Helen, the Royal Traverse was one of the last great problems of Tasmanian bushwalking, something that had never been done. It was certainly kind of her to leave this walk open for later adventurers when you consider that she had, in fact, done this trip herself as part of a much greater trip. As I understand it, Helen and her husband John and two others walked from King William Saddle to Geeveston in eight weeks via the King Williams, the POWs, part of the Franklands, the Arthurs, Federation Peak, and the Pictons. This was in 1963 before the Gordon River Road existed, and their first air drop was at Lake Pedder. They exited the POW Range at Southern Bluff, leaving the southern five miles of the range below the tree line to a crazier generation of walkers, this being their reason for regarding their own traverse as incomplete. By comparison, our trip, including a six-day warm-up in the southern Reserve, was a mere 27 days.

It was that southern five miles of the POW Range between Southern Bluff and Mt Yopyop that especially attracted our attention. It was described most graphically by Reg Williams and Olegas Truchanas in Tasmanian Tramp number 18 as a “low evil ridge”, a “sea of arboreal corruption” and covered in “botanical bastardry”. Reg and Olegas were thought at the time to be the first to bash this ridge, but I have heard of an earlier visit in the late fifties but all details are lost in the mists of time. The same issue of the Tasmanian Tramp also had a Peak Baggers Guide (put in as a joke by Tim Christie but taken unexpectedly seriously by mainland walkers) in which Diamond Peak in the northern POW’s was declared to be a First Class Peak worth 6 points while Mt Yopyop was a Third Class Peak worth 5 points. This had to be checked out!

Packing of air drops began a month or two earlier. On one occasion, I recall that we filled a supermarket trolley at Flemings, Campsie, to overflowing and the bill was a whopping $37, a personal best at the time. On another occasion, Peter and I took a break from packing to go climb the Harbour Bridge by means of a ladder from Hickson Rd to the upper arch inside a hollow steel column in total darkness. After climbing all over the bridge, we walked through the City Circle tunnel from the Harbour Bridge to Central via Wynyard and Town Hall at 3am. No trains came down our tunnel, although we heard one in an adjacent tunnel on the last leg. At Central, there were cops waiting on the Castlereagh St side of the railway, but luckily for us nobody was watching the Elizabeth St side.

The hitchhike to Tasmania involved a substantial detour via Broken Hill and Adelaide on account of a wedding in Adelaide. A former president of SUBW, Graham Beatty, got married on December 22, 1971 (the shortest night of the year) after an exceedingly brief engagement. Carol Pereira (now Carol Isaacs), a very adventurous bushwalker who introduced me to such activities as canyoning and Harbour Bridge climbing, was also invited to the wedding and was also headed for Tasmania, and so we hitchhiked together. Some of the rides were quite off the wall.

At Blackheath, we were picked up by a character out of a Henry Lawson poem, named Ernie Green, who was driving a vintage semi-trailer with a broken muffler and carrying a bus on the back, bound for Mt Isa. At Bathurst, he stopped for several hours to fix the muffler and also a cracked manifold and flat tyre. Later he drove through a downpour without windscreen wipers and then stopped for a few beers at Lucknow until the weather cleared. Next, the nuts on the accelerator pedal came undone and another tyre went flat. Ernie jocularly blamed all this on Carol because, “women are bad luck in trucks.” We asked him why the bus wasn’t driven to Mt Isa. He said that you might as well throw it on the back with the other gear. In fact he and his mates used to save petrol by putting one semi on the back of another and driving in shifts. They once wiped out some overhead traffic lights in Cairns doing this. He had no shortage of outrageous tall stories, and I was inclined to believe all of them.

When we got out of Ernie’s truck at Nyngan after nearly two days, we were seriously behind schedule. At Cobar, when it was clear that no more traffic was headed west that afternoon, we stopped for a refreshing swim at the Cobar Olympic Pool and then camped on the red dirt just out of town. The next day a DMR truck carrying gravel for road construction took us to the end of the gravel-road section of the Barrier Highway 17 miles before Wilcannia and then returned to Cobar for another load. The truck driver was concerned for our safety in the midsummer heat and asked oncoming westbound cars if they could take two passengers, but we were fine as we had plenty of food and water and were ready to walk into Wilcannia in the evening if no ride appeared. We had by this stage given up on getting to the wedding on time and made plans to turn left at Broken Hill and hitch to Melbourne via Mildura. However, we did not have to wait long as a car, with two other hitchhikers already on board, picked us up and was headed directly for Adelaide. The driver was an English tourist who was quite tired and nervous because he had let the young female hitchhiker drive on the dirt-road section of the highway, she having done a bit of uncontrolled fishtailing in the strong crosswinds. At Broken Hill, the five of us had a few beers and a swim in the local pool. Across the border, Carol took the wheel for fifty miles and was able to hold the car steady enough in the crosswinds to let the driver get some well-earned sleep, Carol’s only previous driving experience being in a Volkswagon on a beach. After a third night on the road, we arrived in Adelaide with enough spare time for a shower and a haircut, and Carol got a bit of shopping done. The bridegroom Graham drove from Sydney to Adelaide by the same route as us and saw no hitchhikers at all.

On the day after the wedding, Carol and I hitchhiked to Melbourne in a Monaro LS hoonmobile which did 95mph (153kph) on the Western Highway. Carol was disappointed that the Monaro didn’t do the full ton (161kph) as she had been to 95mph several times before. We spent the night on the campus of Melbourne University where there was a crane that had to be climbed. After a quick plane ride to Devonport, we hitched to Hobart via the West Coast and Queenstown. On the Murchison Highway, our driver was drunk as a skunk and did 95mph (but not the ton) in the wrong places. He did some major fishtailing and collided with several guideposts, but Carol still would have liked him to put in that extra 5mph of effort. We camped at the top of the 99 Bends above Queenstown and the following morning climbed Mt Owen in heavy rain. After that we hitched into Hobart along the Lyell Highway, parts of which were comparable to the Wombeyan Caves Road in those days.

It took a few days to locate Peter and Karsten in Hobart as we kept doing assorted day trips and missing each other’s messages. Carol managed to locate her bushwalking companions more easily. During this time, I ran into Stuart Graham and Bruce Maxwell, who were acting as caretakers for a house on Summerhill Road, West Hobart. They showed extraordinary hospitality to mainland walkers visiting Tasmania. Although Stuart was still based in Sydney at this time, he soon became a permanent Taswegian, as did many other mainland walkers. (I was tempted myself for a while and three years later I took my beautiful young wife on a reconaissance of Hobart suburbia, but the weather was exceptionally uncooperative on that occasion and all plans to move south were abandoned.) When Peter and Karsten were eventually located at the GPO, the five of us had a round of Pakenham Draught ciders in full pint-size (570ml) glasses at the St Ives Hotel in Sandy Bay. Later we located Jim England, who was the pilot who placed our air drops, to see if the air drops were OK. He said that it took him a month to get a good view of the King William III dropsite because of bad weather and eventually had to drop the bags from a considerable height. (With the help of Jim’s aerial photos of the dropsites, we found all our bags in good condition.)

Stuart was very keen on our proposed Royal Traverse and we were equally keen to have him along, especially since we had overstuffed our air drops. Stuart was a very powerful walker with a lot of experience in the Tasmanian wilderness. A few years later, he did epic lilo trips down the Denison and Gordon Rivers and even liloed all the Gordon Splits while the river was low due to the Gordon impoundment filling up. Peter Blackwood was an active member of both SUBW and SUMC, members of the latter club dubbing him Fleabeard. His principal interests were rock-climbing and mountaineering but he had plenty of experience in the Tasmanian scrub. Later he accompanied me on some memorable flooded canyon trips including two reckless attempts to get down Dumbano Canyon in high flood with Joe Friend, Chris Aflecht and others. (The 1972-73 canyoning season was one of the best ever with continuous heatwaves in December and January and numerous tropical storms in February, while the following canyoning season had floods that were too big to handle.) As for Karsten, I did not know him previously and was a little concerned that he had never done a Tasmanian scrub-bash before. But he was very fit and was an experienced New Zealand mountaineer, and Peter had complete confidence in his suitability for the proposed trip. It turned out that Peter’s judgement was sound. Bruce wasn’t interested in the Royal Traverse, but he joined us on the warm-up trip in the southern Reserve, which was quite a decent walk in its own right.

On the evening of New Years Eve, Bruce drove us up to Lake St Clair in an old Commer with a wrecked clutch, which we ended up pushing along the last bit of road into the campsite. On New Year’s Day 1972, it rained all day. Bruce spent the day in the mud under the car while the rest of us watched from a picnic shelter. The next day, the five of us headed off up the exceedingly muddy track to Lake Petrarch and climbed Mt Olympus in clearing weather. There were large patches of deep snow suitable for glissading in Volleys. Over the next four days, we left the comfort of the Reserve tracks and visited Mt Byron, Mt Cuvier, Coal Hill and Goulds Sugarloaf, where we glissaded again on a steep patch of snow. From Goulds SL, we returned to Mt Cuvier and headed north over a scrubby saddle to Mt Manfred, after which we negotiated several sandstone clifflines on the descent to the Lake Marion track. This is all beautiful wild country that is overlooked by the hordes who do the Overland Track. At the time these mountains were totally trackless. The last part of our six-day warm-up followed the Overland Track along the shores of the HEC-raised Lake St Clair back to our starting point.

On our return, Stuart had a change of heart and declined our invitation to do the Prince of Wales traverse, and there was no way to convince him otherwise. He was concerned that he was not strong enough for the heavy packs and unrelenting scrub that was expected. He had read the article by Reg Williams and Olegas Truchanas and knew how bold and tough those guys were. This made me somewhat nervous as I considered Stuart to be the most qualified of all of us and I felt that the success of the trip was assured if he came along. After Stuart and Bruce drove us up to the foot of the King William Range, they wished us well and returned to Hobart. The remaining three of us pitched out tents on a piece of burnt button grass next to King William Creek and spent the evening in silence as we contemplated the remote country to the south in which we would be spending the next three weeks.

Our plan was to peak-bag everything, regardless of whether or not there were points to be gained from Tim Christie’s list. If the southern five miles of the POWs were mandatory for a complete traverse, then so also, we argued, was a corresponding northern extension over a low evil saddle to Algonkian Mountain. On the first day (Jan 7), we bagged Mt King William I and Mt Pitt. The King Williams are mostly open going over dolerite boulders and cushion plants with the exception of one gratuitous 2000ft deep glacial saddle, called King William Gap. The descent into this remarkable saddle was through very tall scoparia and pandanni forest and was surprisingly easy going underneath the canopy. At the bottom, we stayed two nights and had a rest day because Karsten got severe blisters breaking in a new pair of Anson D-Ring boots in the slush on the way to Lake Petrarch. (Peter wore lightweight boots which served him well and I stuck with good old Volley OCs the whole way.) On the following day, we climbed out of the saddle through beautiful tall alpine jungle and proceeded along the range to Mt King William II. Shortly afterwards, the weather closed in and we camped for two days in pea soup. On the fifth day after leaving the highway, the mist began clearing and we reached our air drops near Mt King William III at the end of the range, where we had lunch with a panoramic view of the POWs.

On Mt King William III, the dolerite was strongly magnetic and we could get our compasses to point due south or any direction we wanted. This was not good because we wanted to navigate the descent towards the Denison River with maximum precision. We were aiming for patchy button-grass leads on the plains below and minor navigational errors could cost us a day of hard scrub-bashing in bauera jungle. The 3000ft descent in the afternoon off King William III with 70lb packs took us through all the varied layers of Tasmanian vegetation, with difficulty alternating between easy and hard. It was similar to the descent off the west face of PB to New River Lagoon that I did on a 13-day solo trip a year earlier (before any tracks appeared on PB), but somewhat easier. There was plenty of horizontal scrub at the lower elevations, this stuff always being an entertaining challenge to get through quickly without exhausting oneself.

That night we camped on a small creek in the rainforest. During the night Hughie let us have it and directed a river through Peter’s tent. All our stuff got wet and we made a vain attempt to dry it out over a smokey fire the next morning. So with even heavier packs we set off for the upper reaches of the Denison River. This stage involved delicate compasswork along a subtle westward ridge, something which is not often done on SW Tas trips. It was much more like navigating the vague ridges in the Wollangambe Wilderness of NSW, except that it was clothed in horizontal-choked rainforest. No errors were made, and we emerged on the button-grass patches that we were aiming for, glad to find that the grey bits on the aerial photos were indeed button grass (and not bauera like the “bowling green” on New River Lagoon). Here we camped again.

The next morning, predictions of an impenetrable wall of bauera and cutting grass protecting the shores of the Denison River were happily proved wrong, and we crossed the Denison at an easy ford. The first 700ft up the ridge onto the northern POW’s was covered in a crazy tangled thicket of lichen-covered horizontal scrub. At one point, Peter was crucified on his H-frame pack and needed our help to get him untangled, accompanied by assorted Easter jokes. After the hori eased off, the ridge was mostly button grass and tea tree the rest of the way to the top, where we camped again.

This was the northern extremity of the Prince of Wales Range, but we were not satisfied with starting the traverse here. So we set aside the next two days for the northbound crossing of the low saddle between the POW’s and Algonkian Mountain and back again. Part of this route was choked with tall bauera and was good practice for the stuff we would be doing later in the trip. At the lowest point of the saddle, we crossed two gullies in order to gain access to a more open ridge to the summit of Algonkian. On the return, we found that the gullies themselves were much better going, the bauera giving way to scoparia and pandanni, where we stopped to camp in the 9pm twilight. The next day, there was no way to avoid the arboreal corruption south of the saddle. Having negotiated that, we continued a few miles along the POW range southwards and camped in a wide flat scungy saddle.

The next day, we continued south along the range through moderate alpine scrub punctuated with quartzite spires. Peter and Karsten used their rock-climbing skills to avoid the scrub whenever possible, or just because it was fun to do. I felt more secure in the scrub. We also bagged some unnamed and most likely virgin peaks off the main range (and regrettably placed cairns on them, perhaps removed since, this being a few years before bushwalkers recognised that cairn building in wilderness areas is unethical). After a while, we reached the celebrated Diamond Peak and were eager to bag those six points. Diamond Peak is the middle summit of three beautiful peaks standing on a short ridge at right-angles to the main range. We climbed all of them and spent a long time resting under a natural arch in the outer peak. We climbed Diamond Peak itself by an exposed ramp on its northern wall, the ramp forming one edge of the characteristic diamond shape.

South of Diamond Peak, the craggy POW Range provided some tricky but entertaining routefinding through a labyrinth of chasms and spires. It was like the Beggary Bumps in the Western Arthur Range before the track formed. There was even a Lovers Leap and a Tilted Chasm. Before lunch, we arrived at our second air drop on a wide open moor and stayed there for the rest of the day. Our initial plan was to leave the second air drop unopened and only use it if we were forced to return along the range for some reason. But there were lots of delightful luxury items (e.g., steamed puddings) in this drop, and so we modified the plan. There were also two air drop bags belonging to another party, but they were one year past their use-by date. We learned later that the owners tried to reach the POW Range from the south by following the Denison River upstream from the Denison Gorge but had to abandon this impossible task. Five years later, an SUBW party successfully exited the range by this route when the Denison River was at a very low level.

On the twelfth day after leaving the Lyell Highway, we covered the long easy central section of the range, stopping just before our third air drop near Mt Humboldt. Having two air drops only a day apart, we set off from Mt Humboldt with crushing packs around 80lb. My pack split its sides and was roughly patched with araldite. The route to Southern Bluff wound its way over impressive quartzite sentinels between which were numerous steep chasms and scree-choked gullies.

Water was a serious problem in the POW range. There are no little creeks, lakes or tarns that are abundant in other Tasmanian mountain ranges, despite the very high annual rainfall of this area. Apart from some mist and light drizzle near Diamond peak, we had no rain since before the Denison and we were not going to get any more till the end of the trip. The only available water was in tiny yabbie holes. These we drained with lengths of plastic tubing into a canvas water bucket. Luckily we all brought tubes of different thicknesses and could join them end-to-end. At the northern end of the range, yabbie holes were easy to find and were well stocked, but by Southern Bluff, we were only locating one yabbie hole per day and had to go a few hundred feet down off the side of the range and wait a long time to get a few pints of water. None of us carried proper water bottles because, after all, this is Tasmania, the island that sinks into the Southern Ocean every few days. We were forced to improvise, and my water carrying device was a rusty Milo tin. The scrub was getting dusty and the moss was turning brown. Ahead of us, the yabbie holes ceased altogether and for the next five days, the only water we had (with one exception) was moss juice squeezed through a handkerchief.

Standing on the shoulder of Southern Bluff at the beginning of Day 14 (Jan 20), we could see the southern five miles of the POWs ahead of us. (For this stage, I had a complete set of new clothes, including Yakka Keyman jeans which had a thick denim weave. Also, I put on my third pair of Volleys, the second having been damaged by being placed too close to a campfire at the upper Denison.) Except for the intricate sawtooth ridge leading off Southern Bluff, it is all below the tree line and is mostly covered in tangled bauera and cutting grass. There are occasional bits of horizontal scrub and stunted rainforest which provide welcome relief from the unrelenting bauera. Almost all parties that reach the POW Range enter from the north over the Denison Range and the Spires and return by the same lengthy but relatively straightforward route. (For a while in the 1970’s, there was a controversial track cut from the Jane River to Diamond Peak which provided quick access to the POWs. I don’t know if that track still exists.)

At the southern extremity of the ridge ahead of us rose the evil dark green shape of Mt Yopyop. It was named by Olegas Truchanas after a Lithuanian swear word which was reputedly quite obscene but whose meaning was carefully kept secret by Olegas’ friends. Tragically, Olegas was drowned in the Gordon River while we were doing this trip, and the mountain has since been officially renamed Mt Olegas.

The first day on the southern five miles was devoted to tricky routefinding off Southern bluff. At first we sidled on the eastern side of the sawtooth quartzite ridge and included a 40ft classic abseil over an overhanging moss cliff on our pack-hauling rope. At the bottom we found squeezable moss and topped up our water bottles. Later we returned to the crest of the ridge for a while and then sidled on the easier western side. When the quartzite stopped, the bauera and cutting grass began, although at first it was broken up with button grass and was not too bad. We spent the first night on the last tiny patch of button grass.

For the next three days, we each took 15 minute leads in turn through the bauera. The leads were always in groups of three, first my lead, then Karsten’s, and finally Peter’s. After Peter’s lead, there was a 15 minute smoko during which Peter rolled a tobacco joint. Unlike in other types of scrub, in bauera only the leader does work. Using the weight of his pack for assistance, the leader claws and thrashes and bends the tangled branches forward, forming a tunnel. The little leaves get under one’s clothes and fill every crevice. The rest of the party spend most of the time standing still right behind the leader and only occasionally take a step forward. Such tracks through bauera close up quickly but probably remain as lines of weakness for years (in the same direction as the original party). On the aforementioned 13-day solo trip, I ran into extreme bauera approaching the shores of New River Lagoon. With nobody to swap leads with, I took six hours to cover 400 yards. There is no elegant strength-saving technique for bauera like there is for horizontal scrub, for example. In contrast, four years later a party consisting of myself, Ross Bradstock and Ian (Goanna) Hickson did a 19-day trip from Port Davey to Lune River which included the traverse over the Bobs Knobs to Vanishing Falls. This traverse is also below the tree line and has a reputation for difficulty. But it has no bauera or cutting grass whatsoever and is mostly through quite beautiful and enjoyable moss jungle and horizontal scrub. In those conditions, the leader only does marginally more work than the rest of the party, and so we never needed to interchange leads.

The first day of full bauera was probably the hardest psychologically, while the next two were harder physically. Early on there was a short bauera-free zone which was filled with thin stunted rainforest trees only inches apart, which caused us to crack up with hysterical laughter. On the afternoon of the first day, we ran into a network of horizontal fallen trees. We would balance along these trees looking for the shallowest patch of bauera to jump into. Always we would misjudge the depth and go much deeper than we hoped. This went on for hours and was absolutely heinous. Finally we hit a small patch of rainforest and set up camp and started looking for wet moss.

This is where Karsten earned himself a slab of beer. While I was squeezing moss juice, Karsten went some distance off the ridge and dug a hole in some mud and waited. This hole very slowly filled with actual wet water. It wasn’t enough for chugalugging, but it was nectar for our parched throats and allowed us to cook an edible meal that night. This was the only true water we saw between Southern Bluff and the Denison Gorge.

The next day, the bauera was more intense, but by now we were getting used to it. We settled into the rhythm of the three 15 minute leads followed by the smoko. At the end of that day, we found another tiny patch of stunted rainforest and were looking for a suitable campsite when we discovered a tent-sized wooden platform built five years earlier by Reg Williams and Olegas Truchanas. So we used that. We then searched for suitable moss down the east side of the ridge. After about 300 feet the rainforest terminated in a wall of bauera and so we climbed back to the best piece of moss and filled our water bucket with the thick brown sludge. In a billy full of moss juice, we poured three packets of Maggi Hungarian Beef Goulash soup. It was horrible. It tasted like moss and mud. This patch of moss supplied all our water needs for the next day and a half. That night there was a little bit of mist on the ridge, but not a drop of rain.

On the fourth day after Southern Bluff, we met the tallest and meanest bauera on the ridge, but now our morale was higher and we were beginning to rip into it with confidence. Mt Yopyop was only a mile away and we knew we would reach it that day. I remember on one occasion taking a 17-minute lead because my 15 minutes were up just in front of a humungous cutting grass clump and I wanted to get on top of that before handing the lead over to Karsten. The last few hundred yards were broken up with patches of button grass separated by short sections of extreme bauera. But even at its worst, the bauera never got as tall as the stuff on the north-eastern shores of New River Lagoon. The summit of Mt Yopyop itself was in jungle near the edge of a patch of button grass about the size of a football field. There we camped and had a mostly dry dinner washed down with moss juice from the previous evening.

The following morning, Karsten was ill and could not eat any breakfast. My own breakfast consisted of muesli and powdered milk in a mug full of moss juice. As a result, our descent to the Denison River was quite slow. We chose an obvious ridge leading to the upstream end of the Denison Gorge but this was not a good choice. The ridge stayed in bauera most of the way down while the adjacent gullies would have had the much more friendly horizontal scrub. Eventually the ridge did run into horizontal. While climbing through the branches ahead of the others, I failed to notice that I was not descending at the same rate as before and only when the branches thinned a little did I suddenly realise that I was about 60 feet above the ground. After a hasty retreat, we sidled into the adjacent gully where conditions were quite pleasant and we were soon at the very welcome river. Despite the drought, the Denison River was difficult to cross because it had some rain in its upper reaches while we were in the Diamond Peak area. Here we stopped for the rest of the afternoon and all of the following day. Karsten made a speedy recovery while we prepared delicious tucker using the abundant water.

The range parallel with the POWs on the western side is below the tree line all the way. It has three stages denoted the Norway, Princess and Nicholls Ranges. It is probably bauera all the way. The area receives very few, if any, visitors and it is a safe bet that no part of these ranges has ever been traversed. That state of affairs will probably persist until the whole South West is paved over. Any takers?

The last two days of our trip were easy going over the Hamilton Range. The final ridge down to the Gordon River terminated at 500ft high quartzite cliffs above the construction site for the Gordon Dam. We had one last taste of bauera as we crossed a gully to the adjacent ridge which saw us safely down. It was now lunchtime on the 21st day after leaving King William Creek on the Lyell Highway and the 27th day after starting at Lake St Clair. This was my longest walk in terms of the number of days. Of course, in terms of distance it wasn’t very far at all, around 50–55 miles for the 21-day stage. Walks of this length can be done in a few days in the Blue Mountains.

At the Gordon River, we met a construction worker who said, “One of your mob just got drowned in here a few days ago.” We knew at once who he was talking about. Olegas Truchanas was attempting to canoe down the Gordon River with Kevin Kiernan in order to replace priceless photos that had been lost in the 1967 bushfires. Olegas had done several epic canoe voyages of this type before and was well known to the general public. On his 1958 voyage, he rediscovered the Gordon Splits, which had been forgotton about since their previous visit in 1928. In early 1972, there was an urgent need to show the public the treasures that were being destroyed by HEC vandalism. Already the Serpentine Dam was built and the impoundment was creeping back towards Lake Pedder. Of course, we now know that all their efforts were in vain and Lake Pedder was drowned in April 1972, just over two months later.

After a few rest days at the very hospitable Summerhill Road residence with Stuart Graham and company, I headed off on an eight-day solo walk which was a natural continuation of the Royal Traverse. This was the full traverse of the Wilmot Range and Frankland Range from Mt Sprent to Terminal Peak and then across to Mt Solitary, which is now an island in the Serpentine impoundment. Again the aim was to peak-bag everything within reach. Except for one tent-bound day in the rain, the weather was perfect and everything that was planned was done. There is not much scrub in this range and some of the mild scrubby bits had the beginnings of a faint track (now probably dual carriageway with cloverleaf interchanges). The area around the Citadel, which required an easy exposed scramble, was the most beautiful part of the range, and hard to beat anywhere. I would have liked to linger in this area for several days. The descents off Frankland Peak and Secheron Peak at the eastern end of the range involved tricky scrambles down chasms. This end was not often done in those days because most parties exited the range at Frankland Peak and headed straight for Lake Pedder. These days, of course, there is no good reason for getting off the range early.

On the seventh day, I climbed Mt Solitary along with lots of other people and then camped on the huge beach of Lake Pedder at the northern end. There were many people coming in by light aircraft to see this disappearing jewel. This was my first trip to Lake Pedder, and it was an amazing place to be, but also sad. That night, I remember these giant moths diving into my campfire and wondered if they were unique to this area and about to be extincted. The last day of that trip was an easy walk along the well-worn track to the Gordon River Road. After a few short walks, I returned to Sydney via the Princes Highway, which is not a bad way to hitchhike home if you’re not in a hurry.

Above – Tom Williams on the Yop Yop section of the Prince Of Wales Range. Jan 1981. Photo – David Noble

The southern five miles of the POWs were visited again in February 1977 by an SUBW party consisting of David Noble, Ian (Goanna) Hickson and Peter Woof, the full trip including the King Williams, the Spires and the POWs proper. They got most of the way along in severe drought conditions but had to bail out to the Denison River, which was fortunately low enough to be navigable on foot, about a mile or so before Yopyop. Dave and Ian, joined by Tom Williams and Bob Sault, came back for another attempt in January 1981 and completed the range in quick time. I was in California at the time and I received a remarkable letter from this party, written at the Dr Syntax Hotel in Sandy Bay, containing beer stains, Volley prints and bauera leaves from the summit of Mt Yopyop.