by Don Cameron

At the end of January 1990, I hoisted my Tassie pack and headed to the Apple Isle after which it is named. David Oslington and Ashley Burke had been walking there for some weeks previously. The three of us travelled to Serpentine Dam, the starting point for our traverse of the Wilmot and Frankland Ranges. They flank Lake Pedder on its Western side.

In drizzle and light wind we began climbing Mount Sprent in the early afternoon. However, conditions rapidly deteriorated, and by the time we reached the summit there was torrential rain accompanied by gale-force winds – a good introduction to the vagaries of the Southwest Tasmanian weather for me. The next section of the trip required reasonable visibility for navigation, so we hunted around for a campsite. Rocky crags provided some protection and careful placement of schist slabs filled in the worst of the holes in the ground.

This is where we thought that the night would be spent, but Hughie had other ideas. The Olympus fly could not stand up to the fierce buffering. It was necessary to hold the tent poles to prevent the fly from being flattened. Retreat was the unanimous decision; this was encouraged by Ashley’s account of his Olympus being destroyed by wind while mountaineering in New Zealand. Morale plummeted as we retraced our steps back to the man-made cave at Serpentine Dam. My faith in the state of-the-art bag of nylon and aluminium that was to be our home was shattered.

We took advantage of the first break in the weather around mid-morning and ascended Mt Sprent tor the second time. Again the weather closed in. making navigation on the wide range with a 1:100 000 map difficult. Occasional clear periods afforded magnificent views of the row upon row of ranges away to the west. Moving out of the lee of a ridge onto an s exposed saddle was a memorable moment: firstly due to the cruel, driving rain, and secondly due to David’s remark, “Gee, this rain stings your legs”. But he was wearing overpants, while Ashley and I were in shorts.

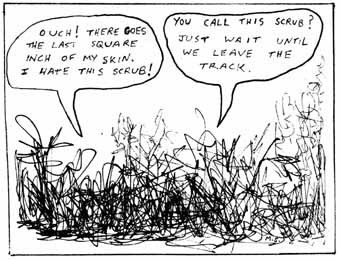

Locating our campsite at Islet Lake was difficult under the prevailing weather conditions. Thick scrub aggravated the problem, but it was great to travel through as it was everchanging and like nothing on the mainland. Just as we were on the point of aborting the search. David yelled out, “Lake!” That evening as I lay under the fly I was dead-dog tired, yet happy, despite water getting into everything and the cramped conditions. It had been a rewarding birthday for me, and I forgave Ashley and David for breaking with tradition and not carrying in a hogget to celebrate with.

Hughie continued to demonstrate the ferocity of the arsenal at his disposal, preventing us from moving on. But Islet Lake! What a superb place to spend time. It is a little tarn that was sculptured by ice during the last ice age and is nestled close to the base of a striking rocky turret. I poked around during a clear period of couple of hours and soaked up the feel of place. Birds could be heard chattering from time to time. I only caught the odd fleeting glimpse of them; this elusiveness of the scarce bird-life in alpine country persisted.

The new day turned out to be a beauty, and we put in ten hours of solid walking. Coronation Peak to the east of the main range is the best side trip of the traverse. With the benefit of the crisp mountain air and no pack to carry, I felt like a mountain goat and enjoyed the climb immensely. From the summit, several tarns were visible far below, surrounded by thick scrub. Here, as was the case most of the time, Lake Pedder was prominent. At first glance, it is an impressive stretch of water. The rudely truncated mountains dotted throughout it sharply remind you of its man-made origin. Ashley aptly dubbed it “Fake Pedder”, and whenever he thought about it his hackles would rise. Only the surface portion of the Fake can be used for electricity generation. This fact compounds the destructive lunacy of flooding Lake Pedder, unique area of outstanding natural beauty sacrificed so that people can run dish-washers and electric can-openers.

The Cupola, a splendid saucer-shaped depression that is covered with button grass and protected from most quarters, was our next campsite. The landscape on the following leg of the trip was spectacular with abundant cliff-faces and tarns. However, the hard climb mentioned in the notes was disappointingly easy. A few hours walking brought us to the Citadel Shelf, the best place to pitch a tent in the Franklands. Shelter from the wind is excellent, a crystal-clear brook makes its way to yet another tarn below the Citadel, a steep rocky mountain that does indeed bear a resemblance to a fortress.

On the way up to the Citadel the usual cool breeze meant that I was wearing a Gortex coat, so you may well imagine the shock that I got on seeing a snake sunning itself on a rock. It was a Tasmanian Tiger snake, much darker than the mainland variety and reputed to be very aggressive. They have evolved to be active at much lower temperatures than most other snakes. When it comes to snakes, I am very much a coward, and this encounter made me keep a good lookout for them. My surveillance paid off as I avoided stepping on snakes in my path several times during the rest of my time in Tasmania.

The morning of the Citadel Shelf was a beauty: cool and calm with soft, friendly clouds drifting across the sky. Yet more tranquil little tarns were sprinkled around. Even though the tarns have only small catchment areas, they are permanently full due to the abundant precipitation throughout the year.

Frankland Peak provided the biggest climb of the trip. Regardless of the weather, we had only a couple of days walking ahead of us. This meant that we could hoe into our tucker well before dark, while enjoying the views of pristine mountains and valleys, and to the southwest, the sea. Dropping off the Frankland Range involved passing through a belt of rainforest. We started on fairly clean track, but this soon petered out. It was good to weave among the mass of vegetation – living and dead, high and low, vertical and horizontal. When there is effort involved, whether it be negotiating thick scrub or climbing a steep ridge, I enjoy what the bush has to offer more than when it is readily accessible.

Signs of man’s presence in the Wilmot and Frankland Ranges are limited. Tracks are present through the few areas of thick scrub and in regions with fragile soils and vegetation. Annoying marks from a pair of boots were occasionally evident – all traces of volleys would have vanished. Chunks of foam rubber mattresses were the only rubbish – carry the bloody things inside your pack! On arriving at the Fake foreshore, we were greeted by a fishing boat, and that universal accomplice of 20th century man – a coke can – along with other rubbish.

The soft, white beaches of Lake Pedder are submerged (until a bushwalker puts a Tassie pack full of explosives to good use). However, a patch of luxuriously spongy plant litter made our last night in the fly very pleasant. Just taking the two-man fly proved to be wise, even though there were three people on the trip.

Back in Hobart, we made the obligatory visit to the Dr Syntax Hotel. After a couple of cool Cascade beers, a main meal with heaps of meat and not a solitary grain of rice, and two helpings of banana splits, for dessert, we were ready for some entertainment. The suggestion of a spot of gambling was agreed on by all parties. Halfway into the foyer of Wrest Point Casino, our passage was rudely interrupted by an oversized bouncer. David was off like a bride’s nightie to try his luck on the roulette table. Seizing the initiative in what was a delicate situation. I boldly inquired of our large escort, “Where’s the $10,000 table?” The man must have been deaf. What was preventing me from having rolls of hundred dollar bills stuffed in my pack or tucked into may grimy bush shorts? Instead of giving us the requested directions, he rudely criticised our dress. Offended, I quickly retorted, “Do you expect me to carry a dinner suit in my backpack?”