By Steve Henzel

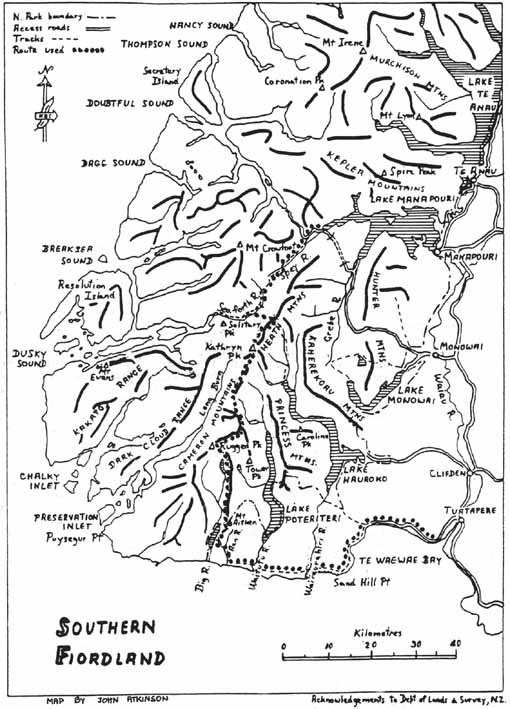

It is Christmas Eve and five of us are sitting around a fire at Lake Innes drying out our damp sleeping bags. The previous night had delivered a tremendous cloudburst that had dumped 12 inches of rain in a three hour drenching. However this is almost normal in Fiordland National Park in the south west corner of the South Island of New Zealand where the average rainfall is 1 inch per day. The park is renowned for the world famous Milford Track and Milford Sound in the north of the park but our objective is the rarely-visited Cameron Mountains in the south and is surrounded by fiords extending inland for up to 50 kilometres. We expect the walk will take at least 18 days if we are lucky with the weather and there is always the possibility that the weather will repel us completely.

Four days earlier, John, Bob and Tony had joined up with Dave and myself in Invercargill after flying in separately from various parts of Australia. A quick trip to the supermarket had seen us stocked up with all our provisions and a taxi ride left us at the end of the bitumen on the road around Te Wae Wae Bay. Our immense packs were shouldered with effort as we commenced several hours walk along the gravel road which led to the start of the track at Blue Cliffs Beach. The track dates back to 1897 when it was constructed to service mining settlements at Preservation Inlet. Later, in 1908 a telegraph line was installed to link the lighthouse at Puyseger Point with Orepuki. Remnants of the wire, insulators and poles still exist along the western section of the track. After the First World War a large sawmill operated at Port Craig. To transport logs to the mill 4 large viaducts were built over deep streams. These viaducts remain today and are part of the southern section of track. Apart from the 4 viaducts and the tramway joining them the only remnants of sawmilling is the old school house at Port Craig. This has been preserved as one of several huts along the track by the NZ Forest Service. We were grateful for its presence as we eased the heavy packs off at the end of the first day. A steady drizzle commenced that evening which continued until lunchtime on the second day. This was an ominous sign at the start of the trip as it was vital that we have fine weather to get over the higher parts of the range.

That second night was spent hiding behind the flyscreens of NZFS hut at Waitutu River. It’s amazing that five tough(?) walkers can be intimidated by a creature as small as the sandfly. The trip to the toilet saw the unfortunate pulling on clothing to cover as much of the body as possible and arming himself with Dimp and a can of Mortein (conveniently left by the previous party) to protect those parts not able to be covered. A liberal blast of Mortein was regularly aimed at the gap at the top of the door to repel all intruders.

A view from the swing bridge just before the hut provided us with our first view of the Camerons, still a daunting distance away. The first half of the next day was occupied by following the old telegraph line west until the Aan River was reached. Here our route headed north into the Cameron Mountains while the track continued west along the coast. We didn’t expect to see another track or hut for another two weeks.

Initially we travelled up through the river itself finding progress quicker along the shingles and occasional pool than along the vegetated banks where large ferns obscured the ground and numerous rocks and fallen branches appeared to be strategically located to find our shins. However a steady rain had developed and as we pushed upstream the river was visibly rising. I had heard that rivers rise and fall quickly in New Zealand but it was still hard to believe that I was seeing it happen as quickly as this.

Late in the afternoon we walked onto the beach surrounding Lake Innes. Vivid green stands of beech jutted into the clear waters of the lake, separating the beaches of amber sand. A choice campsite was selected amongst the beech trees. The coarse granite sand of the campsite sloped steadily down to the lake and all our experience said that this would provide good drainage. But we hadn’t reckoned on what Huey (our weather god) was to throw at us. The heavens opened up as if somebody had turned on a firehose and even the coarse sand could not drain the water into the lake fast enough. A sheet of water over a centimeter high was running down over the sand and through our tents into the lake.

We woke the next morning to find the lake had risen over half a metre and our billies were full of water. With every stream and river in the area flooding and after three hard days of walking, a rest day was unanimously called for. Tony demonstrated his prodigious fire lighting skills by getting the soaked wood soon blazing. And there we sat enjoying the day by drying out our sleeping bags beside the fire and indulging in many cups of tea.

Christmas day arrives with the best of all presents – a fine day and clear, blue skies. Making the most of our fortune we immediately head for the closest part of the range. However, the heavy packs and a long 100 metre climb through the forests mean that we only reach the tops by the middle of the afternoon. Walking out of the stunted beech trees onto the snow-grass tops allows us our first views for days. Behind lies the coastline along which we slogged for days. Off the coast several remote, desolate islands poke out of the grey seas and in the distance Stewart Island can be discerned.

The view ahead is dominated by the Cameron Mountains. The effects of glaciation that dominated the shaping of the area are clearly visible in the U-shaped valley of the Big River and the numerous hanging lakes across the valley. The going now changes from the forests of Beech, Rimu and Totara to the open snow-grass and rock covered ridges of the range. As we proceed along the ridge a wall of afternoon clag rolls in . Once again the firehose is aimed at us as the clouds open up and the heavy rain forces us to retreat 300 metres down off the ridge to find refuge for the night. Merry Christmas indeed!

The next day the ridge is a series of 100, 200 and 300 metre climbs up and down – a roller coaster ride along a knife-edge ridge – but the going is easy and we make good time. As we camp we preview the day ahead. A towering peak lies ahead, half of it seemingly has disappeared into the Big River that lies below leaving just clifflines on the southern side. To make matters worse the next day dawns with high cirrus cloud streaming in from the west – a bad sign in this part of the world indicating that bad weather is on the way – and as we push on towards the peak the weather becomes progressively worse. The peak is too steep on our side and we are forced to sidle around over the snow-grass slopes as light rain falls and a breeze picks up. At regular intervals one of us looses his footing and slides down the slippery grass for several metres before managing to regain control.

The breeze increases into a steady gale and occasional showers of rain are coming through. The weather is turning really nasty. On one occasion Bob sticks his head over a sharp ridge and is immediately blown back. A howling gale is blasting straight up the slope on the other side. Our route leads down the 45 degree slope and the steady, strong wind allows us to confidently stroll down the wet snow-grass slope which would normally be treated with much more respect.

We hide from the weather for the next two days in a deep bowl below the range, grateful to be in Beech forest rather than on the bleak, exposed tops. We are even more grateful to have brought books along to occupy the time during these wet days. The books were brought partly because of our experience in similar situations in Tasmania and Dave and John’s previous experience in this part of New Zealand. Both had walked the Princess mountains to the east in separate trips years before.

At last the weather breaks and we sprint across the tops to the next sheltered campsite. However the bad weather returns that night and another rest day is forced on us. Eleven days are gone and almost a week’s walking lies ahead of us. With time running out we decide we have to push on tomorrow irrespective of the weather. The alternative is to go on half rations of our already meager meals.

The next day arrives, bleak and forbidding, but at least it isn’t raining. Discretion prevails as we depart the tops for the valley to the east. Arriving at the roaring stream we push steadily upstream until arriving at a deep pass in the range for lunch in the rain. Progress has been aided by a well trodden deer trail that makes use of this pass to the west. The rain means that we still wish to stay off the cloud-covered peaks to the north so we choose to follow a small stream that leads north into the range.

The afternoon is easily the worst part of the trip. At some time in the past, half the mountainside has fallen, blocking the bottom two kilometres of the stream. Boulders three and four metres high lie piled up together, covered with 20 centimetre deep moss. It is impossible to tell whether rock or air lies beneath the moss without stepping on it. With gaps metres deep an accident is imminent. And it starts to rain again!

But worse is still to come. At one stage the creek is banked up behind the boulders to form a lake. The water has flooded the gaps in the rock and thick vegetation grows on and around the boulders preventing progress. After a long, hard day this is the last thing any of us want. Nobody wants to lead but it is getting late and there isn’t a campsite to be seen. We push on, eventually breaking free of the tortuous boulders .

Camp is made on a large rock next to the stream with Dave and John’s tent located closest to the water. The rain continues into the night and when the roar of the stream becomes too loud to allow sleep, Dave sticks his head out to see the water has risen to less than half a metre below the door of the tent. Luckily the stream rises no higher during the night.

When the next day dawns bright and clear we are only to keen to get out of the stream and back onto the open tops. The joy of arriving on the tops is complimented by meeting the first people outside our group since lunch on the second day. The two young geologists have been helicoptered into there site and are doing field work for geological mapping of the area. Tony, our party’s geologist, enters into a different language of granite, gneiss and gabbro while the rest of us enjoy a cup of their generously spared coffee. We push on to leave the Cameron Mountains and enter the Heath Mountains. Our campsite is a beautiful lake nestled below Seaview Peak. The hill is aptly named, as it, and the higher Katherine Peak to the north, provide stupendous views of the fiords stretching out to meet the sea, both to the south and west. Looking back we can see the Camerons wedged between two, mighty, glaciated valleys. They look like an impassable barrier to the south so numerous and rugged are the sharp peaks within our view.

We push on but yet another sudden change in the weather forces us to camp high that night. Our protection from the prevailing winds is little more than a slight rise in the ridge but there are no alternatives. The weather continues to be bleak and blustery for most of the next day but when it starts to clear around 4 pm we decide to go for it. A hut lies only 4 hours away but only during a New Zealand summer can you consider starting walking at 5 pm. The days are light from 4 in the morning to after 9 in the evening. We have often started walking at 11, continue to about 7 pm and still have enough light left to pitch our tent and cook.

We walk into the Lake Roe hut at 9 pm much to the astonishment of 5 trampers who thought they had the hut to themselves that night. They are more surprised to hear that we have come from the south coast. Cooking and numerous cups of tea doesn’t see us to our sleeping bags before midnight.

The hut lies on the track joining Lake Hauroko to the Dusty Sound track. We have only to walk out along the tracks to complete the walk. Two days later and we are at Lake Manapouri waiting for the boat to take us into Manapouri at midday on the 18th day. This is perfect timing for a perfect trip.